Micromax Informatics once had a firm grip on the local mobile phone market in India, for a time passing stalwarts like Samsung, icons like Apple and many more to be the biggest handset maker of them all. But a mix of stronger (and cheaper) competition, coupled with the rapid pace of technology development and the ongoing market slowdown, have left it spinning.

While some believe that it still has some life in it yet as a mobile brand, sources and filings point to something else: it’s eyeing up to step into mobility, specifically into the area of electric vehicles.

But that change in gears is also coming with a lot of bumps. TechCrunch understands that the New Delhi-based company has axed dozens of jobs both at its headquarters in Gurugram as well as branch offices across the country, cutting into its ranks in sales, product, testing, R&D and logistics, and the rest of the business. Several top executives including the company’s chief business officer and chief product officer have also resigned in the last some months. Its most recent smartphone model launched as far back April 2022.

Micromax declined to comment about the job cuts and other details of this story.

To the public, for now, the company remains a mobile phone company, although many cracks are showing. Reports on social media show the company’s reluctance to handle consumer complaints. Distributors and retailers are having a hard time with their inventory because there is little demand for Micromax phones from consumers. And basic searches on the Micromax brand on Google from 2008 — its first year in mobile — lay bare the general decline in chatter about the company. There have also been reports about how the company is gearing up, among other similarly struggling older brands, to redouble its efforts to recover.

“[The] market is very competitive now, focused around the top five or six brands,” said Navkendar Singh, associate vice president at market research firm IDC. Micromax, having dropped from its position at the top of that list, is as good as forgotten.

The EV move would come in the form of a new brand and focus, at least initially, on two-wheel electric vehicles, according to three individuals who recently left the company.

A shift to urban mobility from mobile phones would not be the first time that Micromax reinvented itself.

Founded in 2000 by Vikas Jain, Rahul Sharma, Sumit Kumar Arora and Rajesh Agarwal, Micromax first started life as a small IT firm, making its first move into phones only in 2008.

The initial journey of the company relied on low-cost feature phones. Affordable Android smartphones and tablets entered the frame some time after, dovetailing with a rising consumer class in India that wanted the latest gadgets, but didn’t have the money to buy a Samsung, Nokia or BlackBerry device — let alone an iPhone.

The company chose a price disruption strategy to swiftly dethrone Samsung from its leadership position in the Indian smartphone market, making it one of the trailblazers in the first wave of cheap, sub-$200 smartphones. Utilizing its supply chain in China, Micromax launched a range of inexpensive smartphones and tablets that attracted the masses, tapping directly into their aspirational inclinations: some models directly mimicked Apple’s iconic iPhone designs.

In 2014, Micromax poached Samsung’s country head for mobile and digital imaging Vineet Taneja and appointed him the CEO. By 2015, it was selling millions of mobile phones a month and generating around a couple of billions of dollars in revenues in a year. The growth in its business helped the company partner with big tech companies like Google and Microsoft to launch smartphones based on their respective mobile operating systems.

The first market problems started in 2014, when Xiaomi and other Chinese vendors started to get considerably more focused on India, disrupting Micromax in the same way that Micromax had disrupted Samsung before it: with highly affordable, Chinese-made models across different price segments.

Having been a trailblazer by manufacturing some of its models in India, Micromax also worked closely with Chinese suppliers like Tinno Mobile to bring newer lines of low-cost smartphones to the market.

It wasn’t enough, though, and by 2016, Taneja was out.

“China-based vendors managed to get quality devices, high specifications and the latest technology at affordable prices with huge marketing and channel spends,” Singh said. “Indian vendors were just not able to compete in any of these levers — product, marketing, channel, etc. As a result, they lost the market to brands like Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo and Samsung.”

Micromax was challenged also due to a state-level move. The Indian government, in September 2014, introduced its flagship ‘Make in India’ program, schemes to incentivize global manufacturers to localize production in the country. Newer market entrants, taking the domestic manufacturing route with its tax breaks and other incentives, started to roll out even cheaper handsets.

The third big blow came in September 2016, when billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries introduced Jio, its 4G network. Testing on the network was closed to a select group of brands. And Micromax — with no 4G-ready handsets given its focus on the low end of the market — was not one of them.

“Micromax didn’t anticipate the movement from 3G to 4G so quickly,” said Ajay Sharma, former business head at Micromax. Other Indian vendors were also impacted, he added.

The troubles with sales also started to flare up tensions between founders and executives, which in turn impacted Micromax’s attempts to raise capital.

According to the data available on PitchBook, the company raised a total of $98.02 million. The most recent post-money valuation is noted as $745.57 million, although that dates from 2010. Former investors include Peak XV Partners (formerly Sequoia Capital India & SEA), Sandstone Capital and TA Associates. The last audit report filed with the Indian regulator shows that Wagner, an affiliate of TA Associates, sold its entire remaining equity stake to Placid Holdings in January 2020, and that the company bought those shares back from Placid Holdings in March 2022.

The company had been in talks to raise a whopping $1.2 billion from Alibaba. But the deal never closed reportedly due to disagreements between Micromax and Alibaba over future strategy for the business.

All of this was being played out amid the ambitions of Micromax’s founders and management. The company may have gained its popularity as an Indian vendor, but it did not want to remain limited to India.

The company entered Russia, South Africa and the Middle East: it hired former India sales director of Research in Motion (BlackBerry) Amit Mathur as the head of its international business and created a separate supply line to cater to the demand in the global markets. The company also tapped Australian actor Hugh Jackman as its brand ambassador.

Micromax roped Australian actor Hugh Jackman as its brand ambassador Image Credit: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In Russia, where the company became the third largest handset vendor a couple of years after debuting in 2014, Micromax followed in the footsteps of Fly Mobiles, which was also operating in the Russian market, according to a former company executive. Fly Mobiles was originally based in the U.K., but a majority stake in its India and SAARC business was acquired by Indian company SAR Group in 2011.

Within one year of kicking off its global operations, Micromax started creating separate supply lines dedicated to its overseas markets. This helped the company control its volume and offer different models catering to the demand for specific markets. Micromax also started generating profits from its global operations.

However, Micromax’s global market presence began to decline after its business in India experienced a downturn.

“The profits were not to the extent that we could sustain and move to the next level as far as the branding is concerned. We were doing it obviously, but we needed support from India,” the former executive said.

With margins shrinking at the company, in February 2017, Mathur left and was not replaced. Micromax eventually sunset its global business operations.

Some former executives believe that Micromax’s founders could have handled the situation better if they had given a free hand to others coming on board.

That was despite the fact that the founders were working on separate businesses simultaneously. Sharma co-founded an EV startup called Revolt Motors in 2019 (sold to New Delhi-based RattanIndia Enterprises in January). Jain also has accessories-focused startup Play Design Labs, which produces wearables and audio devices.

An angel investor and two-time startup founder who works closely with Micromax said the founders’ decision to run Micromax alongside other businesses suggests a lack of trust and confidence in their own venture.

“I personally felt that when all your energy and fire are there with one particular brand and then every day you want it to grow, then nobody can stop it,” echoed a top-level executive who left the company earlier this year. “If you are not being able to devote that time, how will an organization survive?”

The four founders are said to have different qualities that helped the company compete against global brands in India and international markets. While Jain is good at building relationships, Sharma is stronger at brand building and marketing, Arora at handling the technical side, and Agarwal at managing finance, say sources.

“The good part is they [complement] each other,” a former executive who worked closely with the founders for over four years said.

Micromax co-founder Rahul Sharma Image Credit: Pradeep Gaur/Mint

Home team fumble

In 2020, Micromax attempted a comeback in smartphones in India. But instead of launching new features, it focused on stoking anti-China sentiment, in the wake of a skirmish between Indian and Chinese army soldiers in June.

It ploughed $61 million into the plan with a mantra of “more R&D” to take on Chinese smartphone vendors. Micromax launched two new smartphone models in 2020 under its ‘In’ series to mark its return in the market. To compete directly with Chinese models, both phones were priced in the sub-$150 segment. The company later expanded the lineup to five models.

But the whole endeavor was a flop. And a former Micromax executive said that even if anti-China sentiment was part of the strategy, the timing was all wrong: the launch happened in early November — over four months after the skirmish.

“By that time, the iron had become cold. It, in fact, had a negative impact because the Chinese vendors started saying, ‘we are more Indian than Indians,'” the executive said, referring to Xiaomi’s claim that it made 99.5% of its phones in India.

Then in 2021, Micromax finally teased the launch of its first 5G smartphone. Two years on, that phone has yet to materialize.

Further afield, Micromax was also looking to partner with some carriers in the U.S. to enter North America, according to a person familiar with the plans. That, too, never happened.

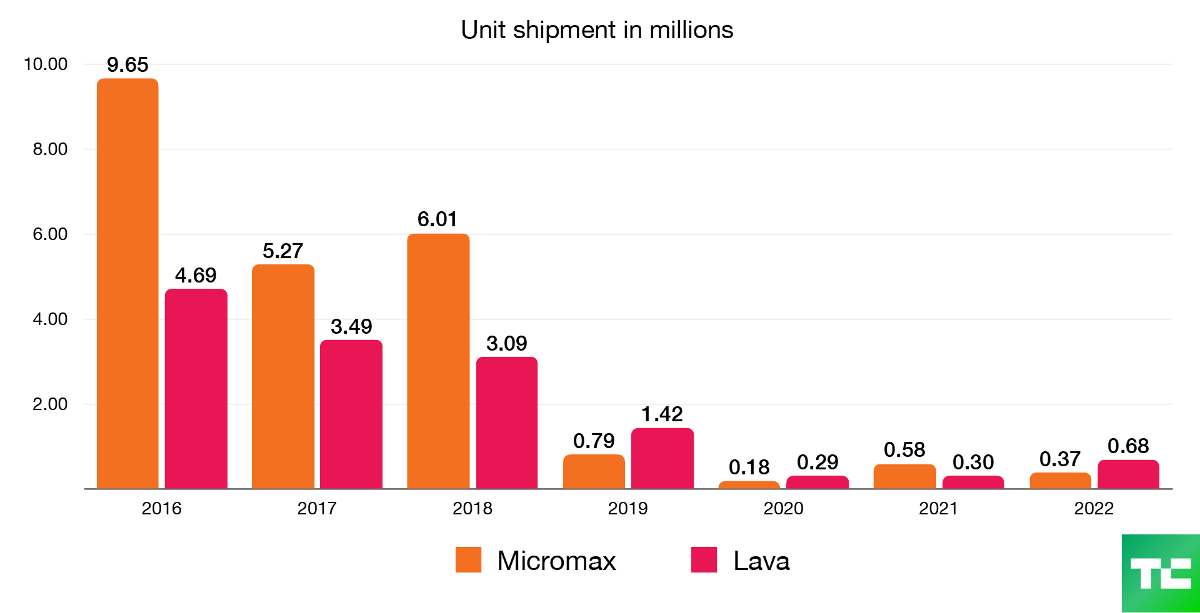

Instead, it continued to see revenues decline. Micromax’s total revenue dropped drastically to a mere $94.26 million in 2022, compared to $1.33 billion in 2016. Smartphone shipments fared no better, dropping to just 370,000 in 2022 from 9.65 million in 2016, according to IDC data.

Micromax was not alone in its struggles to compete against Chinese vendors in India. Lava International, Karbonn Mobiles and Spice Mobility also all threw their hats into the ring. Lava, with a focus on 5G, has seen some growth in recent months; but Karbonn Mobiles and Spice Mobility, the two companies that worked with Google — alongside Micromax — to launch its first Android One program in India, have left the smartphone market.

Micromax and Lava smartphone shipments, according to IDC Image Credit: Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch

Some have fared better. Data shared by market analyst firm Counterpoint also shows that while Micromax saw an 80% year-on-year decline in its overall shipments in 2022, Lava’s smartphone shipments grew 85% year-on-year. The company also recently launched its mid-range 5G phone called Agni 2 to take on similar options from Xiaomi and Samsung. Micromax, in contrast, has had no new models in the pipeline, according to people who worked at top positions in the company until March.

Shuffles and layoffs

While attempting a turnaround, Micromax has also cycled through a number of other executive moves in the last several months, including hiring and then losing both Luke Prakash Andrew as its chief business officer and chief product officer Sunil Loon.

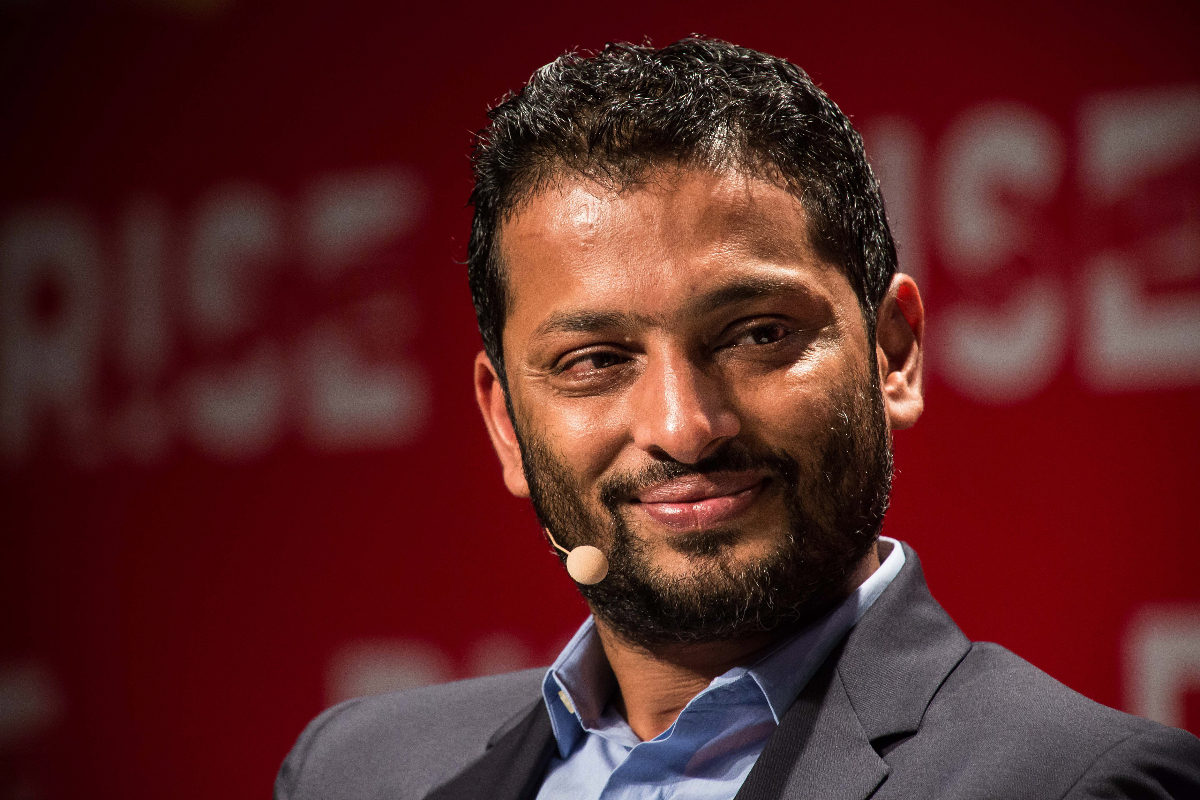

Co-founder Rahul Sharma, who had been the key face of the company for the last several years, resigned from his managing director’s position in April 2021. The board appointed Vikas Jain, one of the other co-founders, as the new managing director, a three-year role that would expire April 2024. Sharma stayed on as a non-executive director, per regulatory filings.

Vikas Jain, co-founder of Micromax Informatics Image Credit: Billy H.C. Kwok/Bloomberg via Getty Images

People familiar with the matter said Sharma stepped down because of the botched comeback plan.

“Somewhere down the line, [the founders] realized that they didn’t have any new things obviously to build up the scale or Micromax again,” a source told TechCrunch.

Sharma was also behind the 2014 ill-fated launch of YU Televentures, a joint venture between now-discontinued operating system maker Cyanogen and Micromax that aimed to take on Xiaomi and its sub-brand Redmi in the country.

And the company has also inevitably had wider layoffs.

Earlier this year, Micromax’s executives contacted some of its employees and asked them to look for new jobs as their existing roles were no longer required. Close to 100 jobs — particularly in the sales and services teams — were reduced as a part of the cost-cutting measures, an executive who also left the company in March told TechCrunch.

The company also started winding down its sales team in various states in the last few months, remaining only in a few states where it had some distributors, the executive said.

The cut in the sales team has made it difficult to shift stock to retailers, which has in turn led Micromax to use the more limited, lower margin cash-and-carry channel, where retailers do not get an option to return any stock left. (Typically, vendors give retailers a time frame to return the inventory they cannot sell.) This has in turn also soured relationships between the brand and its retail channel. Micromax’s existing auditor — SR Batliboi and Associates — also resigned in June, after nearly nine years of working with the company, over not getting their demanded fee, per a recent regulatory filing.

Moving ahead?

The reduction in workers and switching to a new auditor may reduce costs, but it also begs the question of how Micromax will manage its next venture.

Two sources said that Micromax has started renovating one of its offices in Gurugram to kick off its work on the new project exploring the EV market, but few employees remain at Micromax to staff the business transition.

But the transition has already been months in the making. In February this year, Micromax founders Jain, Rajesh Agarwal and Sumeet Kumar incorporated a company named Micromax Mobility, per regulatory filings.

Although Sharma also had a small stint in the EV market with Revolt Motors, his name is not attached to the new venture’s filings.

A source said that Micromax directors started discussions and prepared documentation for the mobility business earlier this year. The company did not brief most of its top-level management about the move.

Jain declined an interview, and he also declined to answer a list of questions shared over email related to recent the job cuts, plans with the EV venture and future of the company in the smartphone market.

TechCrunch also attempted to contact Micromax’s media relations multiple times, with no success.

Micromax’s failure in the smartphone market sends a stark warning to other handset makers that want to compete on price alone. Even if it can draw a line under its own misadventures, it remains to be seen if the company can make the shift to the EV market, which is already crowded.

So as Micromax moves out of the frying pan that is India’s mobile phone market, that doesn’t keep it out of the fire. Those that might pose a threat include Ola Electric, Ather Energy, and traditional automobile players such as Bajaj and Hero Electric.

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/sjNg3tI

No comments:

Post a Comment